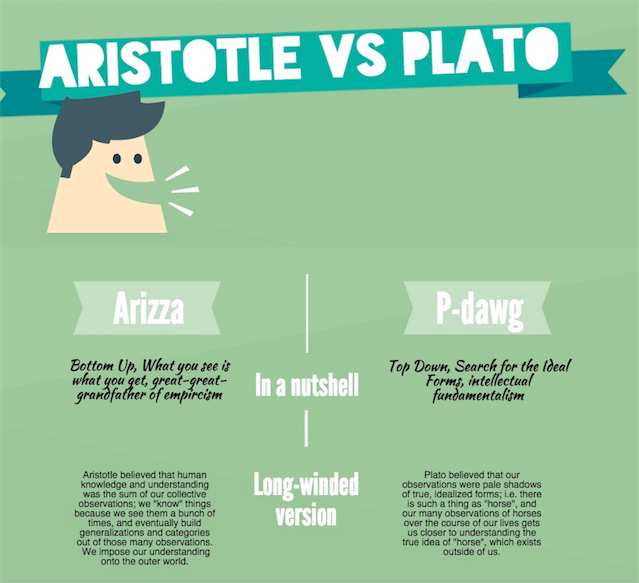

One of the greatest debates in the history of Western philosophy -for many the seminal disagreement - is between Plato and Aristotle. It breaks down essentially as follows:

I heard a fascinating discussion on NPR with Fred Benenson, who translated the entire novel Moby Dick into emojis, and is currently trying to fund and build an emoji translation engine. The host was indignant, asserting that emojis aren't a real language because their meanings are fuzzy and interpretive. She has a point, but it hides the bigger point - her critique applies to ALL language, not just emojis.

I think that most of us, almost all of the time, approach language with our Plato hats on - we assume that words have certain correct meanings, that we can generally expect people to be aware of these meanings, and that when we disagree with people, it's because those other people are stupid and have a wrong-headed view of the world (not because we might be miscommunicating).

I also think that we're totally wrong, and that Aristotle provides a much better lens for looking at the way we use words to make meanings.

How did you learn the meaning of the words you know? You might have looked some of them up in a dictionary, but for the most part, you gained a sense of their meaning experientally, through repeated use and observation; through interactions with others; impressionistically, little by little. Everyone else did too - but they had their own lives and collection of experiences, so chances are, they understand the words you use slightly differently than you do.

Simply put, we want to put objects, emotions, and experiences into huge categories and give identical characteristics to the items in those categories; for instance, we use the words "cute" or "terrifying" to describe different individuals, but we believe that every person we stick that label on shares a common characteristic. Our brains like categories. It makes thinking easy and efficient. But it doesn't take much interrogation to see that this process breaks down very quickly. I'm willing to bet that you've used the words "cute" and "terrifying" in many different contexts with different intended meanings, based on the context, the mode of delivery, the people participating in the conversation, and your personal experience with those particular words. Even inside one human's brain, a single word takes on a multiplicity of meanings that swirl around a vague conceptual area. Imagine how much more problematic this becomes when you start to consider two different people with different life histories, people raised in different cultures, or in different socioeconomic strata.

I guess what I'm really trying to say is that words don't mean anything by themselves - they're symbols invented by humans to represent ideas inside human brains; they're an attempt to build bridges between isolated intellectual units, and although we'd like to believe we're building those bridges using interchangeable parts, we have no way of really knowing what words mean inside other peoples' heads.

For a much more sophisticated discussion on a similar strain, check out the linked Chomsky lecture.

No comments:

Post a Comment